WACC and Beyond: Behind the Curtains of a Compiler

Published:

WACC (officially pronounced “whack”) is a simple variant of the While-like language family that appeared in a series of courses on program reasoning and verification at Imperial. The WACC Compiler project is one of the major group projects for the second year younglings in computing to overcome, and I am glad to say that we survived it with lots of fun and learning a lot.

(FYI: I was credited as one of the bug hunters for the reference compiler script!)

During development and after finishing the project, I came up with some super cool ideas, which I would be discussing later in this post and (hopefully!) get to implement this summer.

If you are not familiar with it, the task is to write a compiler for the WACC Language manually (i.e. craft the scenes from the middle game, such as Abstract Syntax Tree and Intermediate Representation all on ourselves, integrated toolchains like LLVM are explicitly banned for the coursework) with several internal milestones.

The development was splitted into three stages:

- Front-end

- Back-end

- Extensions

We got three weeks (along with other courses and tasks going on - it’s really a busy year) on the previous two stages and two weeks at the end of the term for the extensions.

We were given the freedom to choose a language on our own for development, and compile the source code to one of the three specified assembly languages (x86-64, aarch64 (armv8-a), and arm32 (armv6)). We chose Rust (trust me it’s really worth a try) for development, used the hand-written style recursive descent parsers and crafted the parsing logic ourselves instead of implementing and using ANTLR and other relative parser generator tools, and chose the AT&T dialect of x86-64 for backend output. I will discuss some of our designing considerations below. For the extensions part, our group have implemented numerous local-scale optimisations, and a type inference system, incrementally developed from a limited local scale to globally effective under a monomorphic context to strengthen WACC’s type system.

These choices were indeed helpful and thought-provoking. And after the whole project, I’m now planning to build a WACC Compiler in OCaml, using the more modern choice of LLVM (well, I learnt the compiler principles now and I guess we shall go modern :P) as its IR and actually implementing LOTS OF some possible extensions that we sadly have no time to complete during term time (including but not limited to graph colouring based register allocation, cross-compiler support, and garbage collection).

Designs Explained

Due to internal restrictions, the source code repository of this coursework is not to be published online, therefore we will kept this post at the discussion level. However you can check out the testsuite we developed based on the skeleton examples here, including the additional tests we made for the references.

We were given a detailed (16 pages) specification of the syntax and semantics of the language, some relative definitions, and some other related references. Its syntax was mainly described in Backus-Naur Form (BNF) notation, whilst its semantics were grounded by sets of rules and behaviour restrictions.

To quickly get a rough feeling of how this language is like, here is a sample program from the given set of example programs, illustrating an implementation of simulating fixed point arithmetics:

# This program implements floating-point type using integers.

# The details about how it is done can found here:

# http://www.cse.iitd.ernet.in/~sbansal/csl373/pintos/doc/pintos_7.html#SEC135

#

# Basically, our integer have 32 bits. We use the first bit for sign, the next

# 17 bits for value above the decimal digit and the last 14 bits for the values

# after the decimal digits.

#

# We call the number 17 above p, and the number 14 above q.

# We have f = 2**q.

#

# Output:

# Using fixed-point real: 10 / 3 * 3 = 10

#

# Program:

begin

# Returns the number of bits behind the decimal points.

int q() is

return 14

end

# Because we do not have bitwise shit in the language, we have to calculate it manually.

int power(int base, int amount) is

int result = 1 ;

while amount > 0 do

result = result * base ;

amount = amount - 1

done ;

return result

end

int f() is

int qq = call q() ;

# f = 2**q

int f = call power(2, qq) ;

return f

end

# The implementation of the following functions are translated from the URI above.

# Arguments start with 'x' have type fixed-point. Those start with 'n' have type integer.

int intToFixedPoint(int n) is

int ff = call f() ;

return n * ff

end

int fixedPointToIntRoundDown(int x) is

int ff = call f() ;

return x / ff

end

int fixedPointToIntRoundNear(int x) is

int ff = call f() ;

if x >= 0

then

return (x + ff / 2) / ff

else

return (x - ff / 2) / ff

fi

end

int add(int x1, int x2) is

return x1 + x2

end

int subtract(int x1, int x2) is

return x1 - x2

end

int addByInt(int x, int n) is

int ff = call f() ;

return x + n * ff

end

int subtractByInt(int x, int n) is

int ff = call f() ;

return x - n * ff

end

int multiply(int x1, int x2) is

# We don't have int_64 in our language so we just ignore the overflow

int ff = call f() ;

return x1 * x2 / ff

end

int multiplyByInt(int x, int n) is

return x * n

end

int divide(int x1, int x2) is

# We don't have int_64 in our language so we just ignore the overflow

int ff = call f() ;

return x1 * ff / x2

end

int divideByInt(int x, int n) is

return x / n

end

# Main function

int n1 = 10 ;

int n2 = 3 ;

print "Using fixed-point real: " ;

print n1 ;

print " / " ;

print n2 ;

print " * " ;

print n2 ;

print " = " ;

int x = call intToFixedPoint(n1) ;

x = call divideByInt(x, n2) ;

x = call multiplyByInt(x, n2) ;

int result = call fixedPointToIntRoundNear(x) ;

println result

end

Generally speaking, our design follows the general principles of crafting a compiler and you can find our final report for the project here.

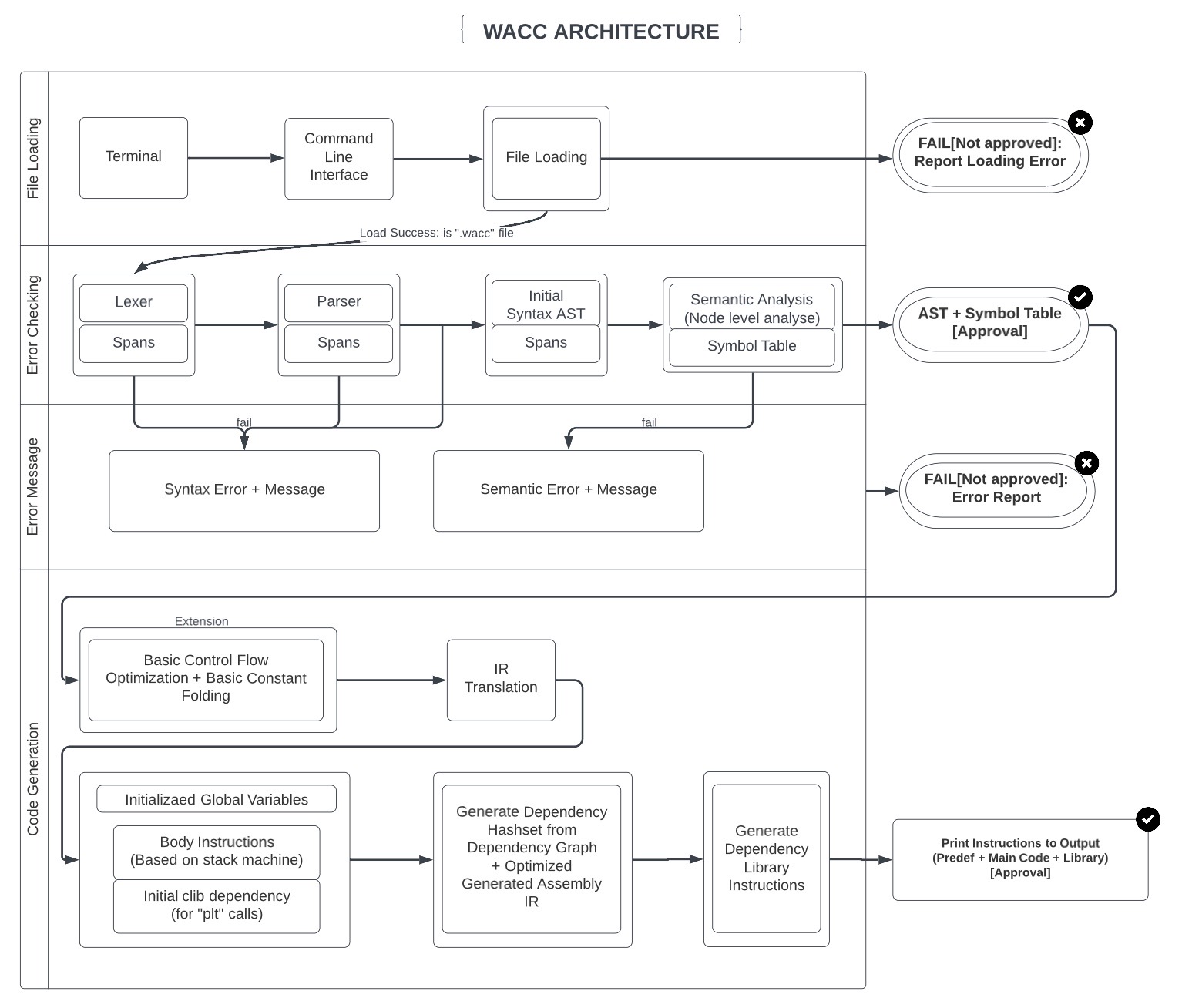

Here is the simplified version of our final flowchart:

Parsers: Recursive Descent and write by hand

There are two mainstream approaches for crafting our parsers: parser combinators and parser generators, both of which are widely used in production. Popular parser generator libraries include ANTLR.

Both of the approaches were available in Rust and have relevant libraries.

- For parser combinators:

nom(more of general usage but could be used for parser combinators),winnow,Chumsky, and lots of other crates. - For parser generators:

lalrpopandpest.

We eventually decided to implement parser combinator approach. Our superherb year coordinator Jamie has written an article on parser combinator design patterns on his paper[1] which greatly inspired us for designing our own parsing framework.

Why Parser Combinators over Parser Generators?

Parser combinators are a viable means of writing efficient and maintainable parsers with good error messages.[2]

Our intuitions:

- Parser Combinators works well with functional programming paradigms (which we really try to practice)

- Although parser combinators may introduce some ambiguity, they are really flexible and extensible. Missing functions and additional features can be easily incremented (instead of crafting the whole design!)

- The behaviour of parser combinators are much more transparent, compared to geneartors.

There has been a long discussion around whether to use parser combinators or generators and it is indeed an interesting topic. This project is mainly for education purposes and we are not intending to argue that we’ve picked THE approach to parser construction. In fact, I would be trying out the Parser Generator approach in the OCaml version of the project!

To be continued…

Compiler Backend

[TODO]

Our current coursework-level design used the stack machine method for register allocation, which is feasible and correct but not the best solution for register allocation, as this approach generally consumes more runtime stack space and is not utilising the full availability of the registers. This might introduce some overheads and

What am I GOING TO IMPLEMENT/IMPROVE?

To be continued…

References

[1] Willis, J., & Wu, N. (2021, August). Design patterns for parser combinators (functional pearl). In Proceedings of the 14th ACM SIGPLAN International Symposium on Haskell (pp. 71-84). https://doi.org/10.1145/3471874.3472984

[2] Willis, J. (2023). Parsley: optimising and improving parser combinators. Imperial College London. https://doi.org/10.25560/110313